Striders

Fleet Steeds of the Vanni

There are few sights more impressive than a seasoned jagun on her strider. In her colorful shell armor, the rider seems more an extension of the beast than its master, controlling it almost entirely through gentle weight shifts and squeezes of her legs. Comparatively, the most accomplished Haciki rider seems brutish, kicking her horse’s flanks and wrenching its head around by the reins.

The seemingly preternatural bond between a Vanni and her mount may be due to a fluke of strider biology – namely, the species’ relatively slow growth rate. Where a horse will be almost full-sized after its first year of life, a strider develops more slowly, growing at almost the same rate as a young human or mab. So, when a Vanni is a child, a strider that was born at around the same time is perfectly proportioned for a child-sized rider.

This explains the Vanni practice of pairing a young mabling with a particular strider so that the two grow up together, fostering a unique connection called “vasika makubo wanacche.” This could be inelegantly translated as “the lost legs that are now found,” and refers to a popular Vanni fable, “How the Strider Got His Legs.” A rider that has fostered such a connection will call his mount “maku” (roughly, “little legs”), which has entered general parlance as a term of endearment.

Of course, this practice has its downsides, as well. A rider that has grown up with her maku can never hope to achieve the same effortless control with another mount. At the same time, a bonded strider that loses its master will usually refuse to accept new riders entirely, becoming surly and intractable.

– Excerpt from A Treatise on the Warmaking Capabilities of the Peoples of the Swaying Veld by Umbheki Ncele, Provincial Syndic of Outer Respite.

Curious Beasts

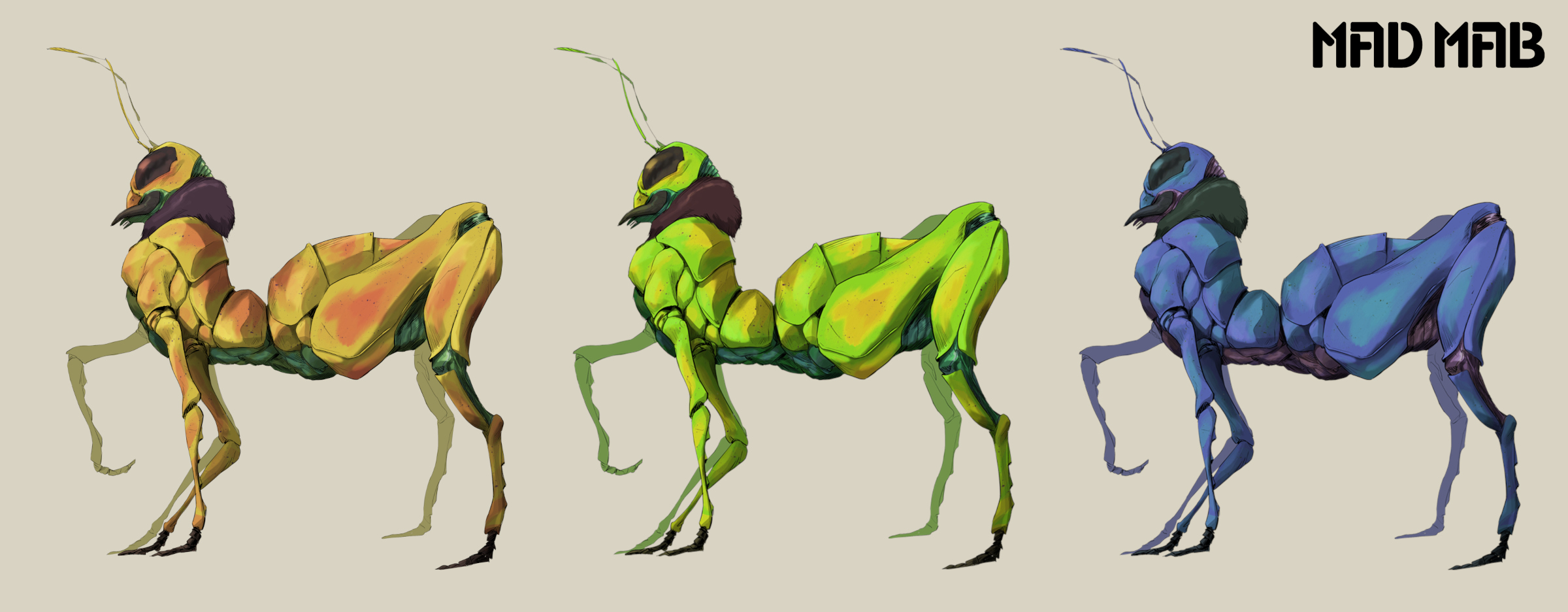

Striders are one of the many large insect species that wander the Swaying Veld. These horse-sized creatures stampede across the grasslands in huge thundering herds, their powerful back legs moving them forward in great bounds. The plates of their thick carapaces come in every imaginable color and pattern, making a large strider herd in motion a dizzying, wondrous sight.

Despite its prominent eyes, a strider’s primary way of understanding the world is through its long antennae, which serve as the creature’s ears, nose and tongue. They are covered in delicate hairs that both pick up minute vibrations in the air and act as compound taste and smell receptors when touched to something. This explains a strider’s constant habit of gently feeling the world around it with these appendages.

Striders are grazing animals, subsisting on the tall grass that covers the central Veld.

Strider with jagun rider. Art by Jennifer Voigt

Companions in Life, Protectors in Death

The Vanni have been riding striders for all of recorded history, and the culture of the clans is inextricably intertwined with these animals. This is especially true of the Hanujadi and Gonyamajadi, whose large, centrally-located reaches take up much of the veld heartland, where these swift insects are plentiful. Here, striders are used by travelers as they navigate the vast distances between settlements, by hunters as they chase down prey, and by jagun as they ride into battle. Striders are rarely employed as draft animals, with Vanni farmers preferring to use stronger beasts like water buffalo or iwo beetles.

Strider shell is a tough, thick material, providing protection from predators in the wild and acting as natural barding in battle. When a strider dies, Vanni will use plates of its shell to fashion armor worn by the jagun, a warrior caste which exists in some form in every clan. While using pieces of creatures that were considered close companions in life as armor might initially seem somewhat macabre, it is considered a way of honoring the strider and keeping the memory of a beloved mount alive. Such suits are sometimes handed down in the same family for generations, each one becoming a relic representing a history of heroic deeds and fearful battles. Peace talks between clans will usually involve the release of armor seized from fallen jagun, and the failure to return captured strider-plate is considered a terrible insult, grave enough to reignite hostilities.

The Shields of Wara

In the centuries since Hacik’s Great Expansion was halted by the all-clan army, a corpus of Vanni law has developed around the protection and regulation of striders as a critical resource. It is generally accepted that striders gave the Vanni an edge against the Haciki forces seeking to encroach on the veld, as the insects are uniquely suited for warfare on the hot, sprawling plains.

To this end, laws were put in place banning the sale or movement of striders out of the veld. A branch of the Reachwatch called the Shields of Wara was established, tasked specifically with monitoring exports and breaking up smuggler rings. What’s more, information about strider husbandry is carefully controlled so that it cannot spread outside the veld.

So far these efforts have proven effective, and no outside power has been successful in breeding striders on a large scale. While the Shields of Wara like to claim this as a victory for their organization, some argue that it is simply due to strider biology, and that the insects require the specific climatic and environmental conditions of the Swaying Veld in order to raise healthy young.

Strider shell comes in every imaginable coloration, though pure white or pure black is extremely rare. Art by Gabriele Barsotti